Tina B.

How would you define Occupy ?

Short answer

Saying ‘no’ to business as usual; protest in the form of non-violent occupation of public spaces; a catalyst for developing a social, economic and ecological sensibility/conscience; a clarion call for change; a set of guidelines for travelers who know the road is made by walking.

Long answer

For me the definitions of Occupy evolved over time. All still apply.

At the beginning, and on a personal front, Occupy was about standing up in opposition to a worldwide, systematic way of operating that felt profoundly wrong and destructive on way too many critical levels (human dignity, socioeconomic justice, survival of the planet and its species, overall quality of life etc.).

Collectively, Occupy could be viewed as the non-violent claiming and holding of public spaces. These occupations depicted a unique form of protest because anyone was welcome to join them and in doing so, become informed, hold open discussions and work towards alternative ways of being and doing.

Within a month, Occupy as practice had turned into the most challenging, absorbing and transformative endeavour of my life. The ‘alternative ways of doing and being’ aspect involved a lot of non-neutral learning, i.e. learning in which I found myself directly implicated as both subject and object.

Attending lectures on environment and economics, for example, I came to realise concretely how my actions (or inactions) as a consumer were directly connected to (and supported) the very problems I was looking to address. Trying to implement something as deceptively simple as active listening brought me face-to-face with my own biases, assumptions and prejudices, many of which I had been unaware of until that point. In addition to the constant exposure to mental diversity and perpetually changing landscape of people, ideas and actions, the radical inclusivity of the camps challenged me to be ever more understanding, open and accepting of difference. In this respect, I consider the occasions of my failures, their nature and the circumstances that surrounded them, as perhaps the most illuminating.

At this stage, I would define Occupy as the catalyst in my starting to develop a strong sense of social and ecological responsibility, a socioecological conscience.

Worldwide, during October-November 2011 and despite (or in spite of) countless incidents of state-sanctioned violence and media-led smearing campaigns, Occupy had attained wide popular support. Vocal supporters included politicians, journalists, academics, artists and activists of all stripes. On a collective level, I would define Occupy at this stage as a loud clarion call for change.

By December 2011, Occupy as both idea and practice had differentiated, specialised, into dozens of single-issue working groups, each of which had taken on a life of its own. As a biochemist, I found it hard to avoid parallels with biological evolution. Except that it felt as if I was watching evolution accelerated by a 100-fold or more. I remember thinking, this is too fast, there’s no time for homeostasis, for any kind of equilibrium or adaptation to take hold. Then again, by virtue of being an extreme environment, we were operating outside equilibrium conditions by definition.

It was at this point too that operational problems started becoming pronounced. Even as Occupy expanded into a brand that was being used on everything and anything, the specific narratives that people and groups developed as a consequence of engaging in their own particular ways of working and being started exacerbating friction and conflict. Differences, until then treated as a source of enrichment and robustness in Occupy, became divisions. There had always been squabbles but over time, attacks intensified and inclusivity gave way to run-of-the-mill fractiousness. A recurrent communication theme pitched real Occupiers against Occupiers seeking to subvert, undermine or otherwise tarnish the movement. At one point, members of one camp (St Paul’s) disowned another (Finsbury). I was part of that conversation and remember feeling split along rational-sounding (makes sense, need to focus and optimise resources) and emotional (this is wrong, we are turning against ourselves) lines.

As attendance at general assemblies dropped, the relationship between the GA (general assembly) and working groups became tense in a way that reminded me of a parent-child relationship, with the parents refusing to accept that his or her children have now grown up and the children rebelling against parental constraints. GA ratification was required to give legitimacy to any action, even when those taking the decisions to ratify had not been involved in the working-group discussion and had no knowledge of the issues, little more than a rubber stamp of approval. Conversely, the culture and hard (patient, committed) work that was consensus became increasingly subject to veto (block) action or, in some working groups, was replaced by majority rule.

It seemed to me that by then, we had lost sight of (and connection to) our overreaching principles and vision. Within and beyond this phase, I would define Occupy as a set of guidelines in search of travelers, the kind (of guidelines and travelers) that know the road is made by walking.

What were you doing before Occupy ?

From 2000 and up until early 2011, I worked as a biochemist researcher in San Diego, California. Later that year, I left my job and moved to Europe in order to support my partner who was taking care of her ailing parent.

Why did you participate in Occupy?

I had been following what had been taking place economically, socially and politically in my country (Greece) with increasing anger, humiliation and despair. I had also found myself at odd times wondering about various forms of material waste and the real cost, the impact in terms of planetary resources/resilience and human suffering/effort, of everyday items such as a lunch-box of sushi, a tee-shirt or an airplane flight. But I was missing a bigger picture and had no platform, no satisfactory means or methods for addressing these preoccupations.

I happened to be in London when I read a BBC article announcing an occupation of the London Stock Exchange the following day. Although I had previously never participated in any form of activism, joining this occupation felt natural because it addressed the core of my concerns. I showed up around noon while the helicopters were circling above and just before the police cordoned off the area around St Paul’s.

What impact did Occupy have on your personal life?

In autumn of 2011, when my partner moved away to nurse her mother full time, I found myself in London alone with time and money on my hands. Within a few days of arriving at St Paul’s and for several months thereafter, Occupy took priority over basic survival instincts (food, sleep), relationships (people close to me felt alienated by my involvement), career and so on. Everything outside Occupy was put on hold.

Did Occupy change the ways you think, feel and interact with the world? If yes, how so? What do you feel that you learned (or unlearned) that was unique to Occupy?

Short answer

Yes, on all fronts. Intellectually, Occupy offered me tools and resources for taking action. Emotionally, it increased my empathy, sense of responsibility and sense of connectedness. Exposure to the people and the camps shifted my perspective in a number of ways, especially towards adopting less polarised and more syncretic/synthetic views and approaches. I left Occupy feeling wiser, more fully human, and with a more expanded view and appreciation of what is possible.

Long answer

In terms of thinking, Occupy served as a crash-course in a broad range of fields (history, political theory, sociology, environmentalism, economics and more), introduced me to new concepts and practices (such as non-hierarchical organisation and communication, consensus, facilitation and restorative justice) and to many examples of grassroots advocacy and activism, both local and international. In short, it offered me the tools and resources for taking informed action.

But by itself, knowledge rarely influences one’s will. Following many actions at and outside St Paul’s, I became aware that appeals to reason (facts, statistics, logical arguments and so on) had by themselves little to no motivational force, i.e. no power to persuade people. This observation was most strikingly apparent in issues of global relevance such as climate change and our debt-based globalised economy but was also evident in everyday inertia, individual thoughtless and destructive behaviors and so on.

I subsequently took a course in social psychology to explore this apparent dissonance. While social psychology provided some insights into the behaviour of people in groups, I found the whole discipline to contain a very skewed and negative view of human nature. Yes, it is important to be aware of one’s weaknesses and blind spots but of equal importance is awareness of one’s strengths and humane potential.

I formed strong bonds of friendship, respect and loyalty with many individuals at St Paul’s. Many of these bonds were based on mutual similarities, others not. It was the people who were most different to me that triggered changes in my identity (my beliefs and value systems), changes that are ongoing. At the time I struggled, and on many occasions failed, to understand and/or accept these behaviours but they nonetheless stayed with me.

I remember Em calling for someone to bring a banana from the kitchen when, during a general assembly, Akira lay on the ground and appeared to be having some kind of attack; the gentle care that she showed him, the steady vigilance. Akira was active with DPAC but St Paul’s experienced a constant influx of individuals who were homeless and mentally or otherwise compromised. At the time, I believed that our time and resources, limited as they were, would have been better spent in organising actions outside the camp than in tending to the needs of people who came to us with addiction, mental health and other issues. I now recognise the value of inclusivity and care, and no longer feel the same way.

I remember Julie calmly explaining the virtues of restorative justice and the importance of letting everyone speak and be heard, remember sitting on the steps of St Paul’s one night when a general assembly involving the finances of Finsbury Square had blown apart all notions of “process” (by this time a dirty word for many if not most Occupiers), sitting and watching her speak through the disruptions, disregard and oncoming mayhem. At the time, I thought she was too lenient, using the wrong, ineffective approaches, out of touch with reality or indulging in wishful thinking. I now look back and recognise my own limitations.

I remember Johnny, at a general assembly discussing the oncoming eviction, speaking out in protest of the homeless, like himself, not being involved in the discussion, not being considered or even heard. I remember feeling how important it was having the chance to hear him speak, how hard it had probably been for him to work up the courage to do so, how habits die hard.

I remember Andria’s unwavering support of Tom and my own bewilderment with this because he was someone I considered a lost cause. Now, one of my strongest regrets from my involvement with Occupy is not giving Tom the floor to speak when I had the chance. It would probably not have done much to change the outcome but I have found myself increasingly shifting towards the belief that the means are more vital and salient than the end.

I remember responses to internal violence: Phil’s grace under pressure, Liz calmly holding her ground while under attack, Obi always signing off his emails with “Yours respectfully”, even in the middle of a flame war, the light humour in the press group’s releases that belied the constant vilifications they received on a near-daily basis.

I remember attending a mediation meeting between St Paul’s and Finsbury Square with a list of proposed items to be addressed in an attempt to negotiate a truce. Tensions had been running high and I was bracing myself for yet another massive clash. I don’t know who had the idea of holding a talking circle but by the end of it, all emotional charge had disappeared. I realised that this dissipation of violent emotions needed to take place every time and prior to any discussion addressing reason.

Such examples formed part of a broader realisation of the limitations of anger and reason, states I was both intimately familiar with and a big fan of. I experienced the understanding that while anger was well suited to recognising injustice and engaging in high-risk, adrenaline-rich activities, i.e. states of combat, it was detrimental beyond this arena and a very poor counselor in matters that required working together and cultivating trust. I found myself favouring its longer-lasting cousin, resolve. Likewise with reason; facts are not something people can unite over and statistics lack the capacity to build human bonds. I found myself gravitating towards shared values instead.

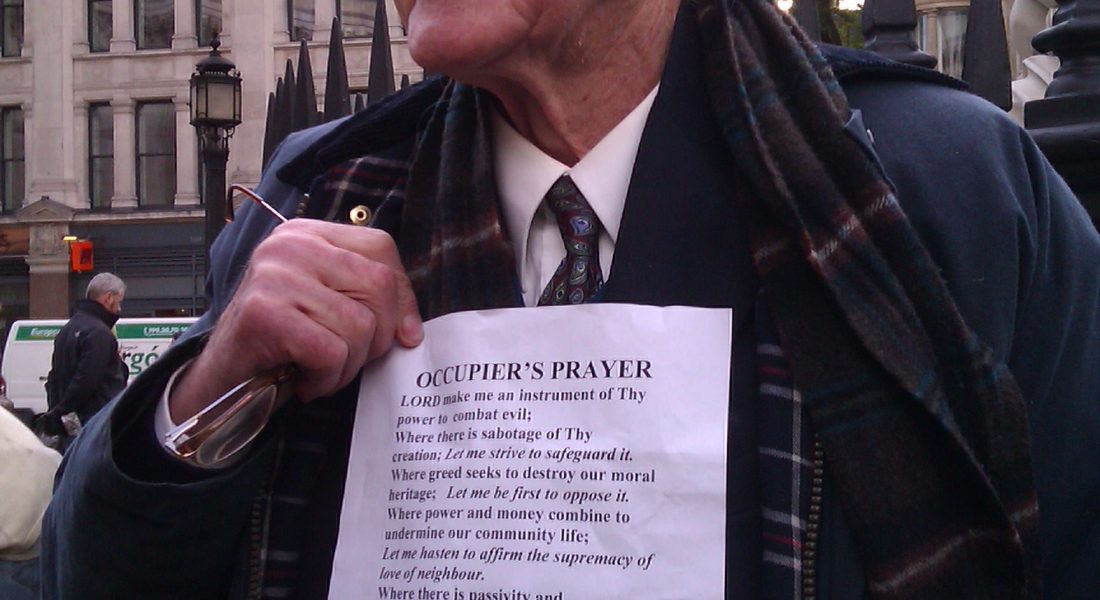

I remember an old guy coming to the camp one day, saying he wanted to celebrate his birthday with us. He called himself John of Purton and carried a sheet of paper on which he had written a block of text under the title ‘Occupier’s Prayer’. At the time, I found him cute but religion was not something that interested me so after exchanging a few words and taking a snapshot, I moved away.

Language can divide us (I found this to be true in Occupy and elsewhere) so sometimes it is important to be able to take a step back and look again at the broader picture. We might find ourselves to be in agreement. I see now that John of Purton was, in his own manner, advocating the same things that we were, the same things the cathedral we had encircled represented and was supposed to safeguard; respect towards our planet and environment (the Lord’s creation), strong and healthy communities (affirmation of the supremacy of love thy neighbour), sharing resources (a spirit of giving as opposed to grabbing), empathy, compassion and acceptance (acting in love and thereby affirming love) as well as the grace and courage to combat fear and darkness, both within and without.

I am still not religious but have chosen this photo as the one that was for me, in retrospect, the most meaningful and instructive.

These and countless other instances of behaviour I can only qualify as graceful, are what transformed my relationship with myself, others and the world around me. The notions of compassion and responsibility, initially weak and mostly abstract, became, over the next few years, more solid and fleshed out, more real. They are continuing to grow. I feel that this affective experience, the physical sensation of responsibility born from the emotional realisation of connection to others and the world at large, is a necessary complement to the intellectual arguments for change and provides a spontaneous source of self-empowerment, meaning and motivation. I could be wrong.

Post Occupy, I find myself unable to compartmentalise as I had done previously. This has especially been the case in “me/us vs them” type of categorisations. My ability to make far-flung connections and see similarities where previously I would have seen only difference has also increased. From this perspective, I view myself and people around me as containing both elements of the problems that we face and elements of their solution.

Following Occupy, my sense of what is possible has also shifted. Again, the examples that contributed to this shift are too numerous to list here. I’d like to stay with one that also addresses the question of what I think was unique to Occupy.

When, following the eviction at St Paul’s Earthian announced his intention to travel the world without money or passport (‘because I am a citizen of the earth and I do not believe that we need national borders’), I didn’t think he’d make it past the Channel. Over the next years, he proved me wrong, reaching Saudi Arabia, Canada, and Japan.

His journey reminded me of a quote by Ursula le Guin:

“I wish we could all live in a big house with lots of rooms, and windows, and doors, and none of them locked.”

This distills Occupy’s vision and spirit for me and, on many luminous occasions at the camps, was what I experienced as Occupy in practice.

What impact do you think Occupy has had on the economic and political situation?

Short answer

Occupy sowed the seeds of a new, highly interconnected narrative that questioned the legitimacy and sanity of our current financial and political institutions. It also proposed alternative futures, many of which are currently being explored.

Long answer

I consider changes in narrative (both personal and collective) as the most profound that can take place. The stories we tell ourselves, what we do and aspire towards as individuals and social beings, inform both our identity and our actions thereby constructing our everyday reality. Social psychology has a term for this effect (narrative transportation theory) and regards it as a suspicious form of persuasion (as used e.g. in propaganda, advertising etc.). But narratives also have the potential to give us the courage to transcend personal and collective limitations.

Occupy changed the dominant global discourse in politics and economics, questioning the sanity of financial structures and policies on the one hand while on the other legitimising discussions on subjects such as debt, income inequality, tax havens/evasion, unconditional basic income and more. While many of these ideas existed before Occupy, they only came into widespread use and prominence through the movement. Perhaps of more critical importance, Occupy brought together activists and non-activists that interacted on a wide range of issues thereby revealing and highlighting their underlying connectivities. It is precisely these dense connectivities (absent from single-issue campaigns) that I believe are likely to account for a long-lasting impact of Occupy’s narrative.

There are many examples of such connections; the relationship between global financial institutions and democracy, between a debt-based monetary system and the environment, between income inequality and mental health, and so on. I would like to stay with one particular example because the connections it makes also pave the way, theoretically and practically, towards a solution.

This example is unconditional basic income (UBI), also known as social dividend or Citizen’s income. UBI is the idea of decoupling employment from income and can be traced back to the 16th century. It can be viewed as both a radical demand (something for nothing) and an obvious one (the right to having one’s basic needs met). UBI was a recurrent theme in Occupy, especially in its relation to debt and the future of work.

As a concept, UBI contrasts the idea of debt as a punishable offense (a guilt-ridden onus borne towards banks by individuals, groups and entire nations), with debt as an obligation, a commitment to care made by society to each and every individual, and an affirmation of the fundamental human right to life. The universal aspect of human rights logically extends UBI beyond the confines of nation-states. In practical terms, UBI juxtaposes income inequality with the idea of the commons, viewing money as a social resource to be stewarded and shared for collective benefit.

In terms of our mainstream political consciousness, both the concept and practice of UBI requires major paradigm shifts from moral arguments and fears of scarcity to a renewed appreciation of the supply-demand dynamic and more. Yet there are signs that such shifts are in the process of taking place.

In 2016, UBI has transformed from a utopian idea to a live policy option. A few months ago, voters in Switzerland rejected a proposal for UBI at a ratio of 3:1. The principle of UBI was recently debated in French Parliament and the White House. It has been discussed as policy in the UK and, in Canada, forms an integral part of the Leap manifesto. Government-funded UBI government pilot experiments are currently underway in Holland, Finland and Canada. Y combinator, a Silicon Valley incubator, is privately funding a similar pilot in Oakland, CA. GiveDirectly is doing the same thing in Kenya.

The interaction of UBI with other systems of social welfare is a subject of discussion in the mass media. More broadly, variations of UBI are being proposed by leaders who recognise the economic virtues of bailing out individuals as opposed to banks (helicopter money) and the importance of public investment (People’s Quantitative Easing). Shorter working hours, a stepping stone in overcoming the main moral argument against UBI, are being revisited under the prism of climate change and the need to reduce growth.

As Jamie used to say to me at St Paul’s, change is all about connecting the dots. It is my view that by its advocacy that highlighted the underlying, dynamic and interdependent connectivities between seemingly disparate issues, Occupy laid the groundwork both for legitimising radical discussions and policies, and for making their implementation more likely.

What, in your view, were the strengths and weaknesses of Occupy?

For a collective description, see here. I would add the point made in the previous section about legitimacy and making radical change more likely.

On a personal level, the strengths for me were diversity (learning, consensus, connections made) and evolution rate (an out-of-control, self-organising entity is very fertile breeding ground). The weaknesses had the same source: diversity (layers of one’s identity challenged or stripped away on a daily basis), and evolution rate (an out-of-control, self-organising entity is ultimately non sustainable, has no time for adaptation).

Given the current political and economic situation, what is your view on what people can do to bring long lasting systemic change?

On an individual level, the famous “be the change you want to see” adage seems most appropriate.

On a collective level, I consider debt as a social and ideological construct to be the linchpin and crux of our current predicaments, so would invite people to engage with this issue in any way they can.

This, in terms of combat. In terms of creating a future, engagement in and with the commons.

Before Occupy, were you involved in activities related to the reasons why you participated in Occupy? (Activist groups, campaign groups, media platforms, volunteering, research, etc)

No

Are you still involved in activities related to the reasons why you participated in Occupy? (Activist groups, campaign groups, media platforms, volunteering, research, etc)

No

Are you still actively working or engaged with people that you met through Occupy?

Yes

What kind of activities are you doing together?

Social

Your age

46

Your nationality

Greek

Where were you living before Occupy?

San Diego, CA

When did you get involved in Occupy?

15-10-2011

Your gender

Female

Where are you living now?

Berkeley, CA